Introduction

In the realm of criminal law, structuring currency transactions to avoid reporting requirements has become a subject of intense scrutiny. A recent case highlights the complexities surrounding such charges, shedding light on the evidentiary standards, jury instructions, and the legal nuances involved. This post delves into the case, analyzing the evidence, jury instructions, and the implications for convictions under 31 U.S.C. § 5324(a)(3).

Video

Secrets Behind Structuring: Don’t Get Caught! ????️ | #Shorts

Transcript:

Let’s talk about structuring under the United States code, an individual who engages in a transaction involving currency and structuring the transaction in an attempt to avoid reporting requirements can be indicted for structuring. By the way that’s United States district court house behind me that’s where you’ll end up if you are indicted for structuring.

Case Background

The case at hand involves a defendant who made a series of cash deposits below $10,000 over a span of seven days, which were intended to fulfill the first payment due on a land-sale contract. Subsequently, the defendant continued to make multiple cash deposits, each below $10,000, over several months to satisfy the second payment. The question before the court was whether these transactions were indicative of structuring intended to evade reporting requirements that are triggered for transactions exceeding $10,000.

Evidentiary Basis for Structuring

The prosecution relied on the pattern of cash deposits to build its case. A total of 22 deposits were made within a week to meet the initial payment, and an additional 38 deposits were made over several months for the second payment. These deposits were consistently kept below the $10,000 threshold. The prosecution argued that this consistent pattern of deposits, each falling just under the reporting threshold, demonstrated a clear intent to evade reporting requirements.

Jury Instructions and Elements of Conviction

The jury instructions in this case were crucial in guiding the jury’s deliberations. The court properly informed the jury of the three elements required to sustain a conviction under 31 U.S.C. § 5324(a)(3):

1. The defendant knowingly engaged in a financial transaction.

2. The transaction involved currency.

3. The defendant structured the transaction with the intent to evade reporting requirements.

Replacing Form 4789 and Intent to Evade

A noteworthy aspect of this case involves the defendant’s alleged intent to evade Form 4789, the currency transaction report that had been replaced at the time of the defendant’s transactions. The defense argued that any reference to Form 4789 was irrelevant since it was no longer in use. However, the court maintained that this did not undermine the soundness of the verdict.

What do the Feds Say about Structuring?

“The definition of structuring, as set forth in 31 CFR 1010.100 (xx) (which was implemented before a USA PATRIOT Act provision extended the prohibition on structuring to geographic targeting orders and BSA recordkeeping requirements), states, “a person structures a transaction if that person, acting alone, or in conjunction with, or on behalf of, other persons, conducts or attempts to conduct one or more transactions in currency in any amount, at one or more financial institutions, on one or more days, in any manner, for the purpose of evading the [CTR filing requirements].” “In any manner” includes, but is not limited to, breaking down a single currency sum exceeding $10,000 into smaller amounts that may be conducted as a series of transactions at or less than $10,000. The transactions need not exceed the $10,000 CTR filing threshold at any one bank on any single day in order to constitute structuring.”

Read More About Federal Structuring Laws Here:

What About Suspicious Activity Reports SAR?

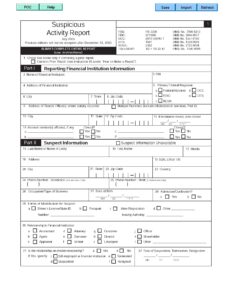

“In April 1996, a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) was developed to be used by all banking organizations in the United States. A banking organization is required to file a SAR whenever it detects a known or suspected criminal violation of federal law or a suspicious transaction related to money laundering activity or a violation of the BSA.”

Download Suspicious Activity Report Form SAR6710-06

Read More About Suspicious Activity Reports SAR Here:

Conclusion

The case exemplifies the complexities involved in proving structuring charges in criminal law. The evidentiary trail of consistent cash deposits below $10,000, combined with accurate jury instructions and the recognition of intent to evade, led to a conviction under 31 U.S.C. § 5324(a)(3). This case serves as a reminder that even subtle patterns of behavior can have significant legal implications. As the landscape of financial reporting continues to evolve, courts continue to prioritize the intent behind transactions when assessing structuring charges.

By analyzing this case, we gain insights into the legal considerations that underpin convictions related to structuring currency transactions to avoid reporting requirements. As regulations and circumstances change, the core principles of intent and evidentiary support remain crucial in upholding the integrity of the financial system.